Over the centuries Liverpool has been able to entertain its people, and visitors to the City, with a remarkable range of varies attractions, performance, and exhibitions. Perhaps though, one of the most bizarre was this one ...

One of the longest-standing and most popular attractions in the North of England was ‘Reynolds Waxworks and Exhibition’. This opened, in 1858, at number 12 Lime Street in Liverpool, directly facing the entrance to the railway station. Owned and operated by Alfred John Reynolds, and later by his son Charles, this was based on Madame Tussaud's Waxworks in London.

Alfred made his own figures, and remarkably lifelike they were. However, Alfred was determined to offer much more sensational subject matter, which would appeal to the thrill-seeking and perhaps jaded tastes of 19th century Liverpudlians. In fact, Reynolds ensured that his exhibitions became increasingly dramatic and bizarre. There was particularly grim representation of Queen Elizabeth signing the death warrant of Mary Queen of Scots, and Henry V111 stood there in the centre of his six wives.

Included in his collection of strange and macabre exhibitions there was a grisly Chamber of Horrors, lit by red and green lamps. His promotional handbills and posters for this were seen all over Liverpool and beyond, and announced chilling wax models and tableaux of ‘murder most foul’ and ‘representations of torment and terror’! An especially popular attraction here was a fully-animated clockwork scene showing an English execution by hanging.

This guaranteed the continuing popularity of his Waxworks, and prompted a sudden increase in other such attractions on the street, each trying to cash in on the craze for the weird and the horrifying. This included the Tivoli Palace of Varieties, which once stood on the opposite corner of Lime Street to the Vines Pub. According to a photograph I have, this advertised an appearance by John (Joseph) Merrick (1862-1890), ‘The Elephant Man’. However, Reynolds’ Exhibition always had the edge!

Reynolds was also particularly anxious to secure a wax model of James Berry (1852-1913), the celebrated and very busy hangman, so he paid this ‘master-craftsman’ the staggering sum of £100 (over £10,000 today!) to sit to have his portrait made in wax. Berry agreed, but Reynolds, who never missed a trick, admitted the public to observe the process, charging them handsomely for the privilege. But the customers got their money’s worth too, because during these sessions Mr. Hangman Berry regaled people with grisly, detailed descriptions of how some of his ‘customers’ had gone to their deaths on his gallows!

In 1899, visitors could have seen ‘The Wax Head of Jack-The-Ripper, modelled from sketches published in the Daily Telegraph, and from witnesses who had actually seen him!’ Which, considering that no one, apart from the notorious serial-killer’s slaughtered victims, had ever seen him was quite an achievement!

The opening hours were from 10am until 10pm, and admission cost 3d (old pence) to view the displays, but 6d (old pence) if you wished to see the live exhibitions and entertainments as well, which were performed twice a day, at 3pm and 8pm. These shows were billed as being ‘of a sensational and horrifying character’, and included a ‘Flea Circus’, and 'Freaks of Nature’, such as, ‘The Norwegian Giant; and ‘Tiny Tim’, who competed with General Tom Thumb from Barnum’s Freak Show, which was then touring the world and had visited Liverpool. There was also ‘The Infant Jumbo’, who was billed as ‘the most wonderful child ever exhibited, who, at the age of 6, weighed over 205 lbs.’; and ‘The Human Atom’, who was 12 inches high and weighed only 22 ounces.

The Waxworks and Exhibition remained very popular throughout the late 19th century and, in 1894, curious Liverpudlians could now see ‘Princess Paulina, the Living Doll’, who was a Dutch Dwarf, also known as ‘Lady Dot’ or the ‘Midget Mite’. She stood at a height of just 17 inches, and weighed only 8½lbs. Sadly, Paulina was only nineteen years old when she died, in 1895. However, she had been such a popular attraction and quite a celebrity during her lifetime that Reynolds made a waxwork of her, which he displayed for many years afterwards. Visitors could also be amazed by ‘Ethnographic attractions featuring a family of genuine Aztecs’! He also presented magnificent marionette shows at Christmas.

Determined to use every modern technological development to enhance his exhibitions, Reynolds also displayed a ‘Breathing Sleeping Beauty’, and an illuminated, sensually and alluringly sculpted wax figure of ‘Ayella, the snake-charming houri’. This model was dressed in a gorgeous and tantalizing oriental costume, and draped in writhing model snakes and alligators. She also had electric fittings that lit up the snakes' eyes. Also on view was a life-sized, mechanical model of the extremely popular, 4 foot 6 inch tall Music Hall comedian and dancer, Little Tich (1867-1928), which danced and bowed.

Amongst other ‘freaks’ who caused a sensation in Liverpool were Millie and Christine McKoy (1851-1912), otherwise known as ‘Millie-Christine, the Carolina Twins’ and also as ‘The Two-Headed Nightingale’. Born as negro slaves on an American plantation in Carolina, these girls were conjoined twins who sang beautifully in perfect harmony. Emancipated in 1866, following the end of the American Civil War, they successfully and happily toured the world, becoming quite wealthy in the process. When they appeared at the Liverpool Waxworks, in 1871, they caused a sensation and Reynolds made a great deal of money from increased ticket sales.

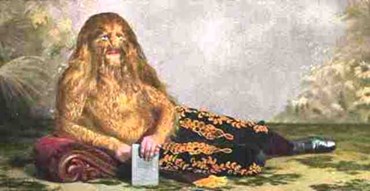

Another of Reynolds’ special star-attractions was ‘Lionel, the Lion-Headed Boy’. He was advertised as being ‘From the forests of Kostroma Russia, eight years of age and bearing a full and completely natural mane of facial and head hair!’ The boy was actually Stefan Bibrowski (1891-1932) from Warsaw. He had been discovered by a German showman who, with the permission of the boy’s parents, put him on show around the world. When people saw him in the Lime Street Exhibition they were told that his unfortunate but entirely genuine symptoms had been ‘caused by his mother witnessing his father being eaten by a lion’.

In keeping with the mores of the time none of these entertainments or freak shows were considered to be salacious or exploitative in any way. In fact, they were regarded as being a completely socially acceptable form of entertainment. Families were welcome and children were particularly encouraged to attend, and Reynolds’ Waxworks was promoted as ‘an educational exhibition designed to inform, warn, and improve the juvenile personality’

The first venue in Liverpool to show ‘moving pictures’’, in 1896, and again in 1897, Reynolds’ Waxworks began showing these as a permanent, featured attraction from 1910. The entire Exhibition survived until 1921, still only charging only 3d and 6d for admission. However, by this time tastes were changing and freak shows were no longer quite as acceptable. The exhibitions were removed and sold, as was the building. However, number 12 Lime Street re-opened, in 1924, now as ‘Reynolds Billiard Hall’. There was a tea room on the ground floor but, by the 1950s, this had become ‘The Empress Chinese Restaurant’. In 1964, the entire block of buildings was demolished and replaced by the new St John’s Market and a multi-storey carpark. Nevertheless, and judging by the current popularity of horrific attractions such as ‘The London Dungeon’, if Reynolds’ Waxworks and Exhibition was to re-open today then I expect it would do a roaring trade!