Most people assume that the famous Liver Birds, which stand on the domes on the Royal Liver Building, where designed and built by the architect of the building ~ Walter Aubrey Thomas: However, this is most certainly not the case, and the story of their true designer is one of sadness and denial.

The ‘Three Graces’ is the relatively new name given to the famous buildings that stand on the Liverpool waterfront, at the Pier Head, and which were all built directly over the former George’s Dock. Individually, these are the Port of Liverpool Building, opened in 1907; the Cunard Building, erected in 1916; and the Royal Liver Building, which was opened in 1911. Of the three, this last building is the most iconic and internationally known.

From the top of the Liver Birds that crown each of its two towers, to its base, the buildings stands at a height of 295 feet (90 metres). This was one of the first multi-storey, reinforced concrete, steel-framed buildings in the world, and its revolutionary design means that its granite exterior is simply cladding. The massive weight of the building is supported on concrete piers that were sunk into the bed of the old George’s Dock to a depth of 40 feet.

The building was commissioned by the Royal Liver Friendly Society to be their headquarters. This company had adopted the Liver Bird as its emblem because this was the name of the local tavern in which the original society had first met.

The building is crowned by a pair of clock towers with, on the east tower and facing the city, one clock face. On the west tower and overlooking the river, there are faces on three sides. This is so that ships on the river can tell the time from any position. Each clock dial is 25 feet (7.6m) in diameter and they are set 220 feet above ground. They are each 2½ feet wider than those on the Big Ben clock tower in London, and each minute hand is an impressive 14 feet long.

Owing to the severity of the weather in the Mersey estuary, each dial has a 3½ ton iron framework, which carries the 660 lbs of opal glass necessary to withstand wind pressure of up to eleven tons per square inch. To celebrate their manufacture, one of the clock faces was first used as a unique dining table, with 40 guests comfortably seated around the perimeter.

The four dials are driven by a single clock mechanism which is named the ‘Great George’. This is because it was started at the precise moment that King George V was crowned, on the 22nd June 1911. This was accomplished via a telephone link with an observer at Westminster Abbey. The huge timepiece was designed to be accurate to within half a minute a year and it is the largest electronically driven clock in Britain.

There are no bells serving the Great George clock but, in 1953, electronic chimes were installed to serve as a memorial to the members of the Royal Liver Friendly Society who had died during the two World Wars, and these are rung on special occasions in the City.

On top of the dome on each of the clock towers stands a gigantic Liver Bird. These are perhaps the most renowned of all the many hundreds of Liver Birds that are to be found across the City. Said to derive from the cormorants that once nested in the old Pool of the Town, or from the eagle crest of King John, the bird carries a sprig of seaweed (‘lava’ in Welsh) in its beak.

The birds on top of the Royal Liver Building are made from hammered copper plates and are bolted together on armatures of rolled steel. They each stand 18 feet high; the head of each bird is 3½ feet long; each leg has a circumference of 2 feet; and the wingspan is 12 feet across. The great birds need to be tied down with cables because a legend says that if they ever fly away then Liverpool would be doomed! They are also of different sexes with the female facing the river. She is waiting for the sailors to return home safely, following their long sea voyages. The male bird stands facing inland. He is watching to see when the pubs have opened!

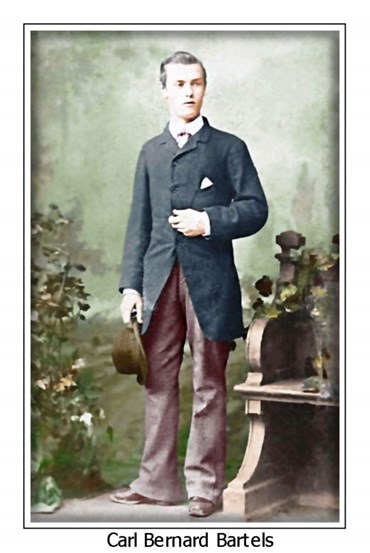

However, for many years the true designer of these famous sculptures was kept hidden, and most people believe that they were the work of the building’s architect, Walter Aubrey Thomas (1859-1934). They are not. They are the creation of Carl Bartels (1866-1955), who was originally denied attribution and credit because he was a German.

Carl Bernard Bartels was a wood carver who had been born in the Black Forest but who had been brought up in Stuttgart. There, he had trained under his father, a gifted and recognised wood carver but, in 1887, Carl decided to emigrate to Britain to begin a new life. So, at the age of twenty-one he came here with his young bride, Mathilde Zappe. The couple were very happy in England and both took British nationality. They settled in the London borough of Haringey where they had a son and a daughter.

The Royal Liver Friendly Society held a competition for the design of the Liver Birds that they wanted to surmount their new building in Liverpool and Carl wanted to submit a design. But first, he had to research his subject, and so he travelled up to Liverpool. In the City’s Town Hall he found a stuffed cormorant and this, together with other images of Liverpool’s corporate symbol, formed the basis of his designs.

When he submitted these, both Thomas and the Royal Liver Society were impressed, and Carl was awarded the contract. The two splendid copper birds were then built by the very skilled Bromsgrove Guild, who were part of the Arts and Crafts movement. This had been led by the artist and writer William Morris (1834–1896), and had been influential in British design since 1887.

However, three years after the opening of the Royal Liver Building, the First World War broke out. Now, anti-German feeling swept across Britain, and German shops, businesses, and homes were attacked, as were many German people. This was especially the case in Liverpool, following the sinking of the passenger liner, Lusitania, which had been struck by a torpedo fired from a German submarine, on 7th May 1915. The Cunarder had been sailing from New York, bound for Liverpool, and she sank with the loss of 1,198 passengers and crew. There were only 761 survivors. In the hysteria following this catastrophe Carl Bartels blueprints and sketches for the Liver Birds were destroyed. His name was also expunged from the records of the Liver Building’s design and construction.

Before this however, at the outbreak of the War, Carl had already been interned as an enemy alien, even though he had been a naturalised Briton for over twenty years. He was imprisoned, with other German Nationals, in a camp on the Isle of Man where conditions were very bad. After the War, Carl was forcibly repatriated to Germany and was made to leave his wife and children behind. He was only allowed to return when a sponsor was found who would act as guarantor for him, and provide him with work. Back in England and reunited with his family, Carl continued carving, and he provided a range of designs for Durham Cathedral and a number of stately homes in Britain.

Carl was still denied credit for the creation of the Liver Birds at the Pier Head and, during the Second World War, he found work making artificial limbs for wounded servicemen. He died in 1955, with only his family recognising the truth about his singular contribution to Liverpool’s cultural and architectural heritage.

However, in the late 1990s, the truth was discovered and, in 1998, his granddaughter and great grandchildren were invited to the City, as guests of honour, by the Royal Liver Society. They dined in state in the building their ancestor had so beautifully embellished, and were also welcomed by the Lord Mayor.

In 2011, on the 100th anniversary of the Royal Liver Building and at a special ceremony in Liverpool, Tim Olden, the great grandson of Carl, was awarded the Citizen of Honour Award on behalf of his forbear. I too am delighted to be able to make the work of Carl Bernard Bartels more widely known and appreciated ~ the true designer of the Royal Liver Building Birds.