This is one of the most controversial stories to have come out of Liverpool from World War Two: I shall leave it up to you to decide whether or not you believe it ...

It is clearly the case that Liverpool has always been home to many wonderful people and to quite a number of eccentric characters as well. Sadly, the City has also had its share of some quite unsavoury people. However, the worst of these residents may well have been the 20th Century’s greatest villain, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945).

Records of Hitler’s early life are limited because, once he became the ‘German Führer’, he had most of them destroyed or re-written. Also, there are a few telling gaps in Hitler’s personal history, particularly from November 1912 to April 1913.

Born in Austria, it is now generally accepted that he was about to be called-up for national service in the military; something he really did not want to do, so it is likely that he simply ran away. Many people now believe that, in fact, in November 1912, and at the age of twenty-three, Adolf Hitler left Vienna and travelled to England. At least, this is what a type-written manuscript seems to say. Produced by Hitler’s sister-in-law, Bridget Hitler (1891-1969), which was discovered in the New York Public Library, in 1973 (Ref No: 81585729). Signed by Bridget, and entitled ‘My Brother-in-Law Adolf’, the accuracy of the neatly-bound pages is questioned by some historians but completely accepted by others.

Nevertheless, Adolf Hitler’s sister-in-law states clearly that Adolf spent that period in the Toxteth district of Liverpool. By the time of Adolf Hitler’s disappearance from Vienna, his half-brother, Alois Hitler Jnr. (1882-1956), had already left the family home, in 1896, at the age of fourteen. Bridget Elizabeth Dowling had been born in Dublin, and she met Alois Hitler in 1909, at the Dublin Horse Show, where he was working as a waiter. The couple fell in love and eloped to London to marry, in 1910.

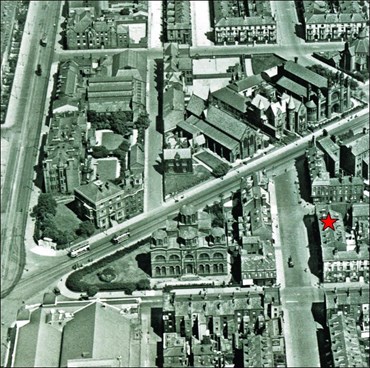

Later that year, the newlyweds moved to Liverpool, where opportunities seemed greater. In the city they rented a flat at 102 Upper Stanhope Street in Toxteth, where they had one child, named William Patrick Hitler. He was born in their small flat, on 12th March 1911. A month after the birth the national census was taken, and Alois, Bridget, and baby William all appear in the official records. Bridget and Alois ran a café in Dale Street;

then a small hotel on Mount Pleasant; and then a boarding house on Parliament Street, but each of these ventures was a failure, so the family had very little money.

Even so, and according to Bridget’s memoirs, Alois's 23-year-old half-brother, Adolf, came to stay with them and their baby. It is Bridget who states that he had come to England to run away from conscription into the Army in his home country: Although other sources say that Adolf was living in Vienna during this period.

Regardless, I worked as the Community Worker for Toxteth, from 1975 to 1983, and a number of the district’s older residents remembered the young Hitler. In one of our general conversations they described him to me as being morose, untidy, and unpleasant — with thin, sharp features – pimply, and with permanently very greasy hair. One old man told me that he was “a total stranger to soap and water”.

Again, according to Bridget’s memoirs, the smelly youth spent hours watching ships on the river, at The Pier Head; or in the Walker Art Gallery gazing at the large painting of 'Napoleon Crossing The Alps', which still hangs in the same place today! He also focussed his attention on the Duke of Wellington standing on top of his high column in William Brown Street: Perhaps these images fed into the young man’s personal ambitions for imperial conquest and military dictatorship.

Bridget and Alois could not stand the grimy youth and, after only around six months, early in 1913, they paid for his return to Germany. Alois even accompanied his half-brother all the way to the boat at Dover, to make sure he got on board and sailed away!

As soon as pimply Adolf returned home he was conscripted into the Austro-German Army, and he ended up fighting in the trenches of the First World War. He actually won a field promotion to the rank of corporal, and was wounded in the groin. He was popularly believed to have lost a testicle as a result, hence the popular wartime ditty, “Hitler has only got one ball …!”

In 1914, Alois Hitler himself left Liverpool for a gambling tour of Europe. Staying in Germany he abandoned his wife and 3-year-old child, leaving Bridget to bring up baby William Hitler unsupported and on her own. He also remarried, bigamously, and had another son. Even so, when he was 18-years-old, in 1929, William did visit his father briefly in Germany.

Of course, in 1933, William’s Uncle Adolf became Chancellor of Germany, the leader of the Nazi Party, and Führer of the Third Reich. With his uncle’s rise to supreme power, it was also in 1933, that William Hitler, now aged 22, travelled to Germany once more, this time though to meet with his famous and powerful relative. The Nazi Dictator gave his nephew a job in Berlin, in the Reichsbank, and William stayed there until 1938: It was then that Uncle Adolf asked him to give up his British citizenship and become a Nazi Party member, in return for a high-ranking job.

William though, suspected that the Führer was laying a trap for him, so he fled Germany and returned to Britian.

Here, he moved to London with his mother, Bridget. In 1939, he wrote a lengthy and sensational article for ‘Look’ magazine, entitled ~ “Why I Hate My Uncle”. This now gave him, and his mother, some notoriety. As a result, in January 1939, and with War on the horizon, millionaire publishing magnate, William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), sponsored William on a lecture tour of the USA, taking his mother along with him.

Hearst and William Hitler made a considerable amount of money from this venture. However, the Second World War broke out, in September 1939, so, and still with their now infamous surname, mother and son were stranded in the USA. When America came into the War, in December 1941, the pair made their home in America:

Perhaps surprisingly, retaining their original family name. Also, William applied for, and was granted, US citizenship again under the name of Hitler. In 1944, he was also allowed to join the American Navy as a Hospital Corpsman.

After the War, William Hitler tactically changed his name to William Stuart-Houston. He met a German girl in America, named Phyllis Jean-Jacques, who had been born in 1923. They married, in 1947 and, still with Bridget, moved to Long Island, New York. The former Hitlers, and Phyllis, now tried to live as anonymously as they could.

William and Phyllis had four sons: The first was Howard, who had been born in 1957. Eventually he married,

and worked as a special criminal investigator for the American IRS. However, he was killed in a car crash, in 1989: He had no children.

The others, Alexander Adolf (born 1949), Louis (born in 1951); and Brian (born in 1965), all remained unmarried and had no children either. However, according to the Family Search website, they all died in 2020:

Even so, it is likely that some if not all of William’s remaining sons may still be alive. Adolf Hitler’s Nephew, William Patrick Stuart-Houston, died in 1987 aged 76, and his wife, Phyllis, died in 2004. They are both buried in a cemetery in New York, together with Bridget, who had died in 1969.

But what of Bridget’s memoirs, which began the telling of all these stories? She seems to have written ‘My Brother-in-law-Adolf’, towards the end of, and just after the Second World War, whilst in America with her son. It is 220 pages long, but undated and unfinished: In fact, it ends on a comma half-way through a sentence!

In 2011, a former editor of the Liverpool Echo daily newspaper, Michael Unger, published a book called ‘The Hitlers of Liverpool’. This was an investigation of the entire story of Adolf Hitler in the City, and the accuracy, or otherwise, of Bridget’s memoirs.

He says ...

‘... It has to be admitted by the sceptics that, as a whole, Bridget’s memoirs are not over-written and in many ways rely on facts so trivial that they would be hard to make up ...

... She writes simply and sensibly, and her description of Hitler’s arrival in Liverpool is circumstantial and convincing in itself’

Four years after Bridget Dowling Hitler’s death, her book was discovered in the New York Public Library by English author, Robert Payne. He went on to publish ‘The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler’, using Bridget’s notes, and being the first to re-tell the ‘Hitler in Liverpool’ story. That the Hitler’s lived in Stanhope Street, and that William was born there, are absolute facts, as is everything else I have said about them. However ~ is the story about Adolf Hitler coming to Liverpool and staying in Toxteth just as true? The evidence is certainly convincing, but it is not conclusive ~ so I leave it to you to make up your own minds.

But there is a final twist to this bizarre story:

The last stick of German Bombs ever to be dropped on Liverpool fell on 10th January 1942: They landed on Upper Stanhope Street and destroyed and badly damaged a number of houses, including number 102 ~ the Hitlers’ former home! Only a grassed-over plot of land remains where their house once stood ~ in the heart of a modern housing estate in Toxteth.