There are many sites of Christian pilgrimage throughout Europe, but few can be older than Saint Patrick’s Cross, in Liverpool. Located now in a tiny and obscure cul-de-sac known as Standish Street, which sits off Crosshall Street in the city centre, can be found a small, beautifully-maintained garden. It is here, many people believe, that in AD 432, and on the instructions of Pope Celestine, St Patrick preached his final sermon before setting sail on a treacherous voyage to Ireland, to convert the people there to Christianity.

Patrick was born in Roman-occupied Britain, although the precise location is uncertain, as is the year of his birth, although, this is generally accepted to have been sometime between the years 376 and 405. Venerated for many centuries, especially by Irish Roman Catholics, there are many legends associated with this popular saint. These include the story that he banished all the snakes from Ireland, driving them into the sea, and that he used the three leaves of the shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity.

In his own writings Patrick describes how, at the age of sixteen, he had been captured from his home by pirates and sold into slavery in Ireland. Trapped there for six years he worked as a shepherd and developed a strong Christian faith. However, one night whilst he was asleep, an angel visited him in a dream and told him how to escape. When he awoke he followed the angel’s instructions precisely and indeed found his way home to Britain.

Wanting to learn more about Christianity, he travelled to Gaul (modern France) where he studied under Saint Germain, who was Bishop of Auxerre. Twelve years later he returned to Britain. There, he felt a calling to return as a missionary to Ireland, and the Pope confirmed this. It was then that he was sent back to Ireland on a mission that was to last for thirty years.

It is thought that Saint Patrick died between 460 and 493, and is said to be buried in the cathedral in Downpatrick, in County Down in Northern Ireland. His annual feast day is boisterously celebrated around the world, especially in Liverpool, on March 17th.

For centuries before the Reformation, and for centuries afterwards, although then in great secrecy, Christians from all over Britain, and abroad, would come to the obscure site outside what was to eventually become the town of Liverpool. Here, they would worship around a commemorative cross that had been erected to the saint. Although there are no records stating when the monument first appeared, presumably it was a stone cross, perhaps set on steps or a pedestal.

Around the cross these pilgrims would give thanks for Patrick’s life and work, and pray for themselves and others. Until the 19th century, this part of Liverpool remained outside the Town boundary, in what was still a rural part of the surrounding countryside. Nevertheless, the position of the cross appears on the earliest maps, showing that it was a significant local feature.

But, during the Puritan era of the 17th century and the Jacobite Rebellions of the 18th century, to be found worshipping at such an obviously Catholic site would have been severely punished. In fact, it was only after the final routing of the Scottish Catholic Rebels, in 1745, that hostility towards Catholics began to relax somewhat. Although damaged, a portion of the cross seems to have survived through these turbulent times. There are reports of it as late as 1775 but, soon after this it disappeared, although its original location remained a site of pilgrimage.

In 1791, the passing of the Roman Catholic Relief Act allowed Catholics to worship openly once again, provided that their chapels were registered with the authorities. Eventually, and with the subsequent passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act, in 1829, Catholics were also finally allowed to vote and sit in Parliament.

It was after this that Catholicism began to become accepted again, and the local population of Catholics was suddenly swelled to very large numbers, with the influx of hundreds of thousands of desperate, starving people into Liverpool, fleeing from the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840s.

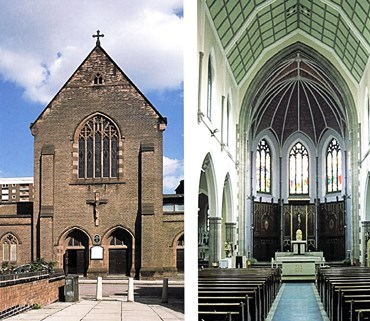

It was then that the site of Saint Patrick’s Cross, in its previously out-of-the way backwater, became a centre of settlement for these Irish Catholics. Knowing of this holy place, dedicated to their Patron Saint, thousands of them moved into the area. Soon, streets of terraced and back-to-back houses covered the once rural landscape. The location of Saint Patrick’s cross now became the focal point of this new community and, in 1860, a Church was built over the site. This was Holy Cross Church, and its altar was placed directly over the sacred spot.

The new church served the large Catholic community, which was made up not only of Irish people, but also of a significant number of Italian families that had settled in the district. These people created a part of Liverpool that became known as ‘Little Italy’.

The church was destroyed by a Nazi incendiary bomb in 1941, but was completely rebuilt in 1954. However, with the decline of Liverpool during the 1970s and 1980s the population of the area rapidly reduced. So much so that the Roman Catholic Archdiocese could no longer justify keeping Holy Cross Church open and, in 2004, and in the face of much local opposition, the church was demolished.

Nevertheless, members of the congregation and other people from the remaining community were determined not to let the significance of the location, or of their local parish, vanish under the bulldozers that were now knocking down their streets and homes. As the once-long streets were replaced with the tiny cul-de-sac of Standish Street, with its dozen or so attractive bungalows, these people decided to recreate the site of pilgrimage.

This is why, in the centre of this secluded and now little-known close is a small, well-kept area of lawn and flowerbeds, surrounded by low railings and shaded by trees. Here, as well as some memorial plaques and tablets, is a large sandstone cross that originally stood inside Holy Cross Church. The tiny garden is also home to part of the foundation stone and stained glass from the church. As well as this, two time capsules are buried in the ground, containing other artefacts from this once-important parish and its congregation.

However, the most powerful object to be seen in this very special memorial garden is contained within a large, transparent, vandal-proof display-case. This stands against a tall, brick wall on one side of Standish Street. Inside this is a beautifully-painted, lovingly-carved, life-size Pieta, which is the name given to a statue of the Virgin Mary cradling in her lap the crucified body of her son, Jesus Christ ~ ‘Pieta’ translates as ‘pity’.

Whether you have a faith or not, and whether or not that faith is Christianity, I suggest that most people would be moved by this celebration of community and of religious belief, as well as by the silent tranquillity of the garden; hidden away as it is, from the noise and traffic of Liverpool’s busy, city-centre roads.